One of the best preserved and largest in the entire Roman empire, the amphitheatre of El Jem is a major symbol of the height of Roman Africa, which added its own particular touch to Roman culture. It is also a prime example of the best of Roman architecture, and sheds valuable light on those moments of collective madness that constituted the Roman games.

At the heart of an arid and monotonous plateau, surrounded by modestly sized buildings, the great amphitheatre of El Jem has always shocked travellers with its size.

The amphitheatre was partly gutted in the 17th and 19th centuries by the beys of Tunis to stop rebel tribes from taking shelter there. It is said that Dihya, the famous Berber queen, was besieged there during the Arab conquest of the 7th century.

The amphitheatre of El Jem is the only one in the Roman world to be built entirely from dressed stone, without the use of bricks. The unit of measure used, the Punic cubit, is another local characteristic.

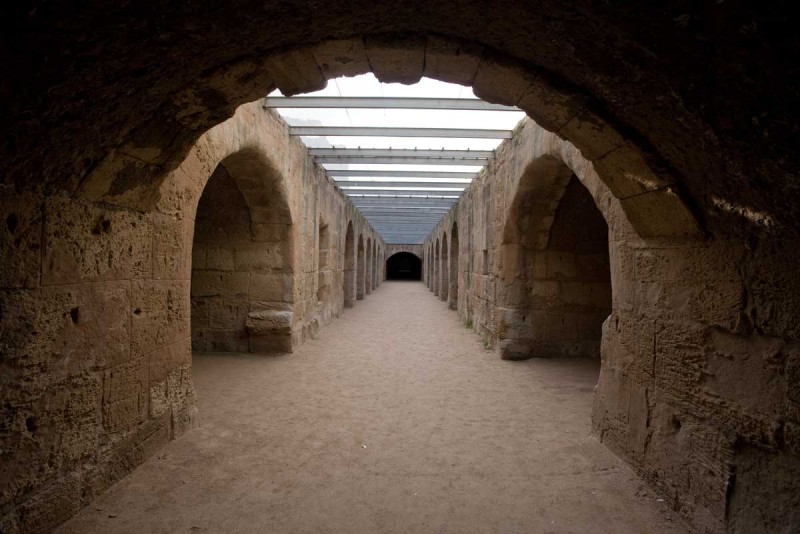

A vast ellipse whose largest axis measures 148 metres across, the amphitheatre of El Jem has preserved intact its arena, its underground chambers as well as a large portion of its facade and its terraced stands.

It is built entirely from eolianite sandstone. This stone with a warm sandy colour is brittle and weak, which explains the massive architecture, with deep and narrow arcades which create fascinating plays of light and shadow.

The imposing facade is soberly punctuated by engaged columns.

Unlike the Colosseum of Rome, which superimposes the three classical orders – Doric, Ionic and finally Corinthian –, El Jem’s is limited to two styles of column, Corinthian and composite. This commitment to simplicity raises up the beauty of the stone, giving the monument harmonious qualities that have long been admired by travellers and historians.

Built at the beginning of the 3rd century A.D., the amphitheatre of El Jem also benefited from several decades of experience from the Roman architects and engineers.

In its structure, where the equal number of vaults and arcades cancel out the mechanical forces acting upon the facade; in the ingenious arrangement of its entrances and corridors, allowing the rapid entrance and exit of thirty thousand spectators, it is more elaborate than its counterpart in Rome. The multiple entrances and stairways, specific to each floor, allow the public to directly access the different stands.

The service corridors, dressing rooms and wild animal cells are further examples of the progress achieved in the design of amphitheatres.

Arranged under the arena when the structure was designed, they greatly facilitated the organisation of the shows. In this way, the wild beasts could be hoisted directly into the arena using lifts, and servants could freely move around the subterranean galleries covered by a removable floor without crossing the processions which opened the games through the ceremonial entrances found at each end of the amphitheatre.

Staged fights with wild beasts were particularly popular among the inhabitants of Roman Africa. Less interested in gladiator combat, they were fond of “venationes”, shows of wild beasts attacking their prey, or reenactments of hunts whose heroes, the “bestiarii”, were adored by the public.

These scenes are widely represented in Tunisian mosaics, especially those discovered in and around the El Jem site.

This amphitheatre was the crown jewel of the ancient city known as Thysdrus, where villas as large and luxurious as those in Carthage could be found; villas adorned with opulent mosaics in finely nuanced colours, faithfully depicting the life and concerns of their contemporaries.

Thysdrus grew rich thanks to the olive oil trade. A land where olive trees were cultivated since Punic times, Tunisia became Rome’s main supplier.

Thysdrus also occupied a strategic location, at a meeting point of six Roman roads, between the vast olive groves of central Tunisia and the coastal ports. The city experienced a rapid expansion and would become an ephemeral regional metropolis, before fading from memory after the 3rd century.

The Golden Age of Thysdrus – around the 2nd and 3rd centuries A.D. – was also that of all Roman Africa whose influence can be seen in places from the art of mosaic – which achieved its most prestigious form in Tunisia – to literature, notably with the Christian writers Tertullian and Saint Augustine.

With its exceptional dimensions and its architectural perfection, the amphitheatre of El Jem is a major sign of the singular position occupied by Ancient Tunisia.

The arena and the underground chambers are exceptionally well preserved. Remarkably functional and with a monumental appearance, the cells and service corridors were arranged under the arena when the building was designed (older amphitheatres would place them outside or under the stands, a less convenient position for the organisation of the games).

The province of Byzacene – the area of Thysdrus (El Jem) and Hadrumete (Sousse) – excelled in the art of mosaic. It is the origin of a “floral” style enriched with plant motifs and arabesques. Among its favoured themes, one can find wild beast fights and the procession of Dionysus, a very popular god who, as a child, received the power to tame wild animals.

Like modern football stadiums, amphitheatres had to allow the peaceful entry and exit of an excited crowd of tens of thousands of spectators. The flow of spectators would spill out into galleries before running into different sections of the stands through openings known as “vomitoria”.

The harmonious nature of the facade sets it apart. It draws upon only two architectural orders, compared to three in the Colosseum of Rome: Corinthian (with acanthus leaves) on the ground and third floor, and composite (combining volutes and acanthus leaves) on the second floor and probably on the upper floor; no longer standing.

© G. Mansour, “Tunisie, patrimoine universel”, Dad Editions, 2016

The amphitheatre of El Jem was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

More about the World Heritage Sites in Tunisia